Time arrives before anything happens. It shows up early, settles in, rearranges the day around itself. You learn it through how the body prepares. Through the way the chest stays slightly lifted, like it’s waiting for a tap on the shoulder. Through how often the jaw tightens when the phone lights up. Through the reflex to count days without meaning to.

Empire works through this kind of time. It lets it sink in slowly. It gives people enough room to adapt, enough repetition to make endurance look like a personal trait. Lives stretch around renewal dates and review periods. Everything keeps moving, but nothing quite lands. You learn how to hold your life lightly, how to keep your belongings minimal, how to stay ready to shift without being told to move.

People live for years inside extensions. Inside temporary permissions. Inside measures that circulate without ever settling into something solid. Life fills the space anyway. Dinners get made. School lunches get packed. Work schedules get memorized. Love keeps happening. All of it unfolds on ground that never fully firms up. You learn to distribute your weight. You learn where not to lean too hard.

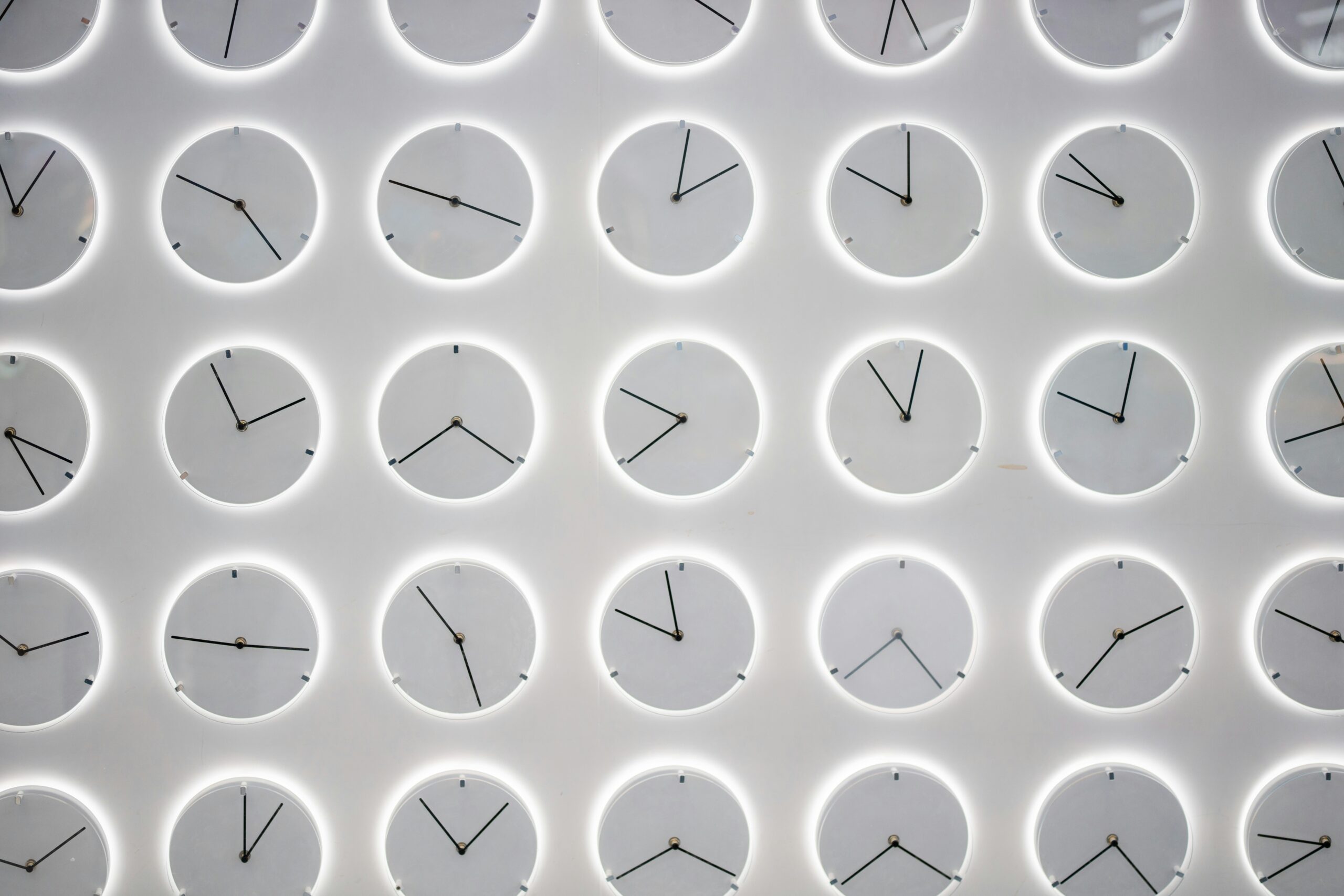

Joy still arrives, but it comes with an internal clock already running. You feel it tick while you’re laughing. While you’re planning. While you’re letting yourself believe something might hold. Celebration becomes careful. Plans stay provisional. Even rest carries a low hum of alertness, as if the body doesn’t quite trust that it can go all the way down.

This kind of time wears people without leaving marks you can point to. It teaches the body to stay available. Sleep thins out. Attention fragments. You start measuring life in cycles you didn’t choose. Renewal cycles. Processing cycles. Waiting cycles. Each one asks for patience. Each one takes a little more capacity with it.

Policy relies on this. Fatigue funnels what feels possible. When energy gets spent managing uncertainty, very little remains for anything else. The week becomes the unit of survival. The future starts to feel abstract. You make decisions based on what requires the least explanation, the least exposure, the least risk of being noticed.

Urgency moves unevenly through this system. Some situations stop everything. Others stretch on quietly, absorbing days, months, years. Loss waits its turn. Harm gets filed, deferred, assigned a new expected timeline. You feel the delay in how long it takes to breathe normally again, in how quickly hope retracts when it gets too loud.

The language surrounding all of this stays calm. Dates appear. Updates get promised. Progress gets implied. These words move smoothly through official channels. They sound steady. They invite trust. They ask for composure. They ask people to keep showing that they can handle it.

And still, time gets made elsewhere. In kitchens where stories don’t arrive in order. On dance floors where the body follows sensation instead of sequence. In care networks that move when someone needs something, not when a form clears. Memory bends time. Touch compresses it. Grief stretches it. None of this asks to be scheduled.

These practices don’t wait for recognition. They happen because life keeps insisting. Because care has its own tempo. Because people stay with each other even when everything else feels provisional. These rhythms don’t resolve the waiting, but they interrupt its authority.

Empire manages time by distributing it unevenly. By deciding who gets to arrive and who must remain in motion. Who is allowed to settle and who must stay ready. Who is worn down slowly enough that it looks procedural. Paying attention to time means noticing how power moves quietly, through calendars, deadlines, queues, and the long spaces in between.

There isn’t a clean ending to this. Time under empire leaves residue. It stays in the muscles. It shows up in how cautiously people plan, in how often joy gets delayed, in how carefully hope is rationed. Naming that doesn’t make it disappear. But it does bring the clock into the room. It lets the weight be felt together.

And sometimes, that shared awareness is where movement begins.